Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

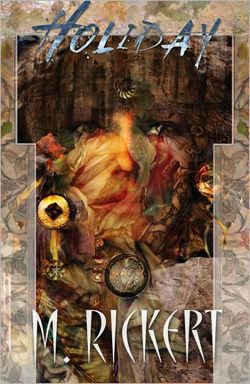

Today we’re looking at Mary Rickert’s “Journey Into the Kingdom,” first published in Fantasy and Science Fiction in 2006. Spoilers ahead.

“The first ghost to come to my mother was my own father who had set out the day previous in the small boat heading to the mainland for supplies such as string and rice, and also bags of soil, which, in years past, we emptied into crevices between the rocks and planted with seeds, a makeshift garden and a “brave attempt,” as my father called it, referring to the barren stone we lived on.”

Summary

On his daily coffeehouse visit, Alex glances at a wall display of not particularly inspired still lifes. More interesting is the black binder labeled “Artist’s Statement.” At his favorite table he reads a handwritten document called “An Imitation Life”:

Agatha lives on a rocky island, daughter of lighthouse keepers. One day her father sails for the mainland to get supplies. He returns in a storm, dripping wet and repeating to his wife, “It is lost, my dear Maggie, the garden is at the bottom of the sea.” He sends Maggie to tend the light; while she’s gone, Agatha watches him slowly melt into a puddle.

Maggie knows her husband’s dead even before his body’s found on the shoals, clutching a bag of earth. Agatha sprinkles the earth by the door; weeks later the whole barren island blooms with forget-me-nots. Maggie says it’s her father’s gift. And Father still visits, leading other drowned ghosts to lament their fates as they melt by the fire. Every morning Maggie and Agatha wipe up their puddles and return the salt water to the sea.

One ghostly visitor’s different, a handsome young man with eyes as blue-green as summer. Offered tea, he begs Agatha instead for a kiss. She gives it, feeling first an icy chill, then a pleasant floating sensation. The young man stays all night, unmelting, telling the two women stories of the sea. In the morning he vanishes. When he returns the next night, looking for another kiss, Maggie demands to hear his story.

Ezekiel tells his tale. He hails from the island of Murano, famous for its glass. His father was a great glass artist, but Ezekiel becomes even greater. Jealous, his father breaks Ezekial’s creations each night, and finally Ezekiel sails off looking for freedom. His father pursues and “rescues” him. Ezekiel murders the old man and throws his body into the sea. Unfortunately Ezekiel falls overboard, too, and goes down to the bottom of the world.

Story told and Maggie off to tend the light, Ezekiel steals more kisses from Agatha. Maggie tells Agatha this must stop. First, Ezekiel’s dead. Second, he killed his own father, not a good sign. She forbids their love, alas, the best way to make it grow. Agatha’s not even swayed when Maggie delves into her book of myths and i.d.s Ezekiel as a breath-thief. These vampiric spirits suck breath from unwashed cups or, far worse, direct from the living through kisses, gaining a sort of half-life. They’re very dangerous, since each person has only so much breath allotted to her.

Agatha’s love is stronger than her fear, however, or her common sense. She sneaks out for a last night with Ezekiel, full of ecstatic kisses. In the morning she follows him to the bottom of the sea. He turns on her in anger, for what use is she to him dead? Agatha, shattered, returns to Maggie dripping. She feeds on her mother’s kisses until Maggie collapses in her black dress, like “a crushed funeral flower.”

Agatha escapes to the mainland and wanders from menial job to menial job, always staying near her ocean. She never steals breath from the living, subsisting on the breath left in cups, which “is not, really, a way to live, but this is not, really, a life.”

Back to Alex, transfixed by the “Artist’s Statement.” He becomes convinced that one of the baristas, also calling herself Agatha, is the ghost of the story. She admits to being the “artist” but insists her “statement” is mere fiction. She’s no ghost, but runs from his request for a kiss.

Alex is recovering from his wife’s death and his own subsequent “weirdness.” He avoids Agatha until a chance meeting in the park. Alex surreptitiously watches her sip his breath from a shared coffee cup.

Their friendship grows over park meetings and moves on to a dinner date at Alex’s house. After dessert, he whisks out rope and duct tape and ties Agatha up. She struggles wildly, insisting she’s not dead, no breath-stealer. Alex isn’t convinced. He drives her to the ocean, hauls her to the end of a secluded pier, and throws her into the black water. The look in her wild eyes haunts him as he returns home to collapse weeping. What has he done?

The sound of dripping water rouses him, and he opens his eyes to see Agatha soaked and bedraggled. She found a sharp rock at the bottom of the world, she says, and freed herself. Alex took a big risk back at the pier, but hey, he was right about her, about everything, and does he have any room in that bed?

He nods. Agatha strips and joins him, cold at first, then warm, then hot, as they kiss endlessly and Alex feels himself growing lighter and lighter, as if his breath was a burden. And then, “the cinder of his mind could no longer make sense of it, and he hoped, as he fell into a black place like no other he’d ever been in before, that this was really happening, that she was really here, and the suffering he’d felt for so long was finally over.”

What’s Cyclopean: Agatha gets most detailed when describing the source of her not-life: “…I breathe everything, the breath of old men, breath of young, sweet breath, sour breath, breath of lipstick, breath of smoke.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Misogyny is our prejudice-of-the-week: Agatha has the worst taste in dead (or soon-to-be-dead) boyfriends.

Mythos Making: Terrible things come out of the ocean, and some of those things are terribly tempting.

Libronomicon: Agatha’s mom has a big book of ghost stories, probably the most practical item in their lighthouse abode. Agatha, meanwhile, hides her creepy ghost stories in the descriptive text of mediocre paintings. “I was trying to put a story in a place where people don’t usually expect one.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Alex questions his sanity—perhaps not as much as he should—as he tries to get his sorta-girlfriend to admit her corporeally-challenged nature.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

One of these weeks, we’re going to cover a story in which all the characters make really good choices. Where you don’t have to be an idiot, or unable to resist forbidden knowledge, to regret being a protagonist for the rest of your days. In a true cosmic horror universe, all the human reason and genre-savviness in the world shouldn’t be enough to guarantee safety from Cthulhu.

This is not that week.

For those who think of this Reread as a demi-objective review series, this is also not that week. My reactions to “Journey Into the Kingdom” are quirky, personal, and deeply colored by the expectation that all these bad-decision-making people are about to show up dripping on my porch. Readers not currently exasperated by other people’s bad decisions (and not completely turned off by Alex’s unique approach to ghost identification), will likely appreciate the story’s emotional and atmospheric intensity more than I did. After all, it made our reading list based on a recommendation from Ellen Datlow on Necronomicon’s “Future of Weird Fiction” panel, and won a World Fantasy Award besides.

!LiveAgatha has plenty of excuse for her bad choices: she’s a teenager living on an isolated island, and Wayward Terrible Pickup Line Ghost is the first guy who’s ever shown interest in her, or even been in a position to show interest. She’s certainly not the first teenager to fall for a terrible, charming guy, and suffer as a result.

Wayward Terrible Pickup Line Ghost has no excuse for his bad choices, unless you believe him about his father destroying all his glasswork. Which I don’t: his story reeks of self-justification and a persecution complex. Death hasn’t improved his personality, or his choices. His “you’re no use to me now” post-coital rejection of Agatha… seems like something he probably did to women when he was alive, too. The parallels to common attitudes toward virginity are probably no coincidence.

!DeadAgatha is actually making reasonable choices, I guess, for a breath-drinking ghost spurned by her dead one-night stand. She’s got a pretty good hunting technique too—drinking from dudes who are “the only person who understands me” when they turn out to be just as obnoxious as her first. (Do I believe her claim to have never done this before? I do not.)

Alex has plenty of excuse for his bad choices: he’s in mourning for his wife, and deeply depressed. He’s certainly not the first person to get into a stupid, self-destructive relationship under those circumstances. His brilliant plan to make Agatha admit her nature via a traumatic kidnapping-and-drowning scheme, I have less sympathy for. Maybe if that’s the only way to get your girlfriend to suck out your life force, you should just… not.

Speaking of Alex’s execrable behavior, I do find this story’s treatment of misogyny very interesting, and both effective and problematic. It’s not the standard terrible-man-gets-his-comeuppance plot, at least. Both Ezekiel and Alex treat Agatha terribly, mirroring real-world behaviors that are all too common. Ezekiel values her innocence and the life she can give him, discards her when he’s taken both, and blames her for everything. Alex stalks her obsessively. He wants what he thinks best for her, in a way that masks his own self-destructively selfish desires, and forces her into following his for-your-own-good script. The particular strategy that occurs to him… probably says something about him as a person, too. That scene has its intended effect—shocking the reader not only with its suddenness, but through the contrast with how a scene like that usually plays out. But I hate how neatly it works out for him. He gets exactly what he wants—and that bothers me, in spite of the fact that what he wants is a really terrible idea.

Anne’s Commentary

If it’s at all comprehensive, no wonder Mother Maggie’s book of myths is such a weighty volume. The chapters on ghosts alone keep her reading until dawn—and Agatha—find her hunched over the tome with dark-circled eyes. Has there ever been a human culture that didn’t hope and fear—perhaps simultaneously—that some part of us persists after death? And not only persists, but preserves the identity of the departed one, his or her memories, his or her essential selfness? If the particular culture is thrifty of spiritual essence, it might imagine souls being recycled into new bodies, or reincarnated. If the particular culture is lavish, it might allow for unlimited numbers of souls but envision other places for them to go postmortem than the family’s basement (or attic, or fancy marble tomb.) We can’t have the ghosts of thousands of generations cluttering up the place. Or can we? If ghosts are like angels, an infinite number of them could waltz on a dance floor the size of a pinhead. And if said ghosts are like dust mites, they could be crawling all over our houses, and us, and we’d never know it. Unless, that is, we employ microscopes or EMF sensors to destroy our blessed ignorance.

For the sake of spectral breathing space, let’s say most souls hie them to heaven or hell pretty soon after death. That still leaves plenty of ghosts who hang around the living and make their presence known, sometimes with beautiful pathos, much more frequently by making a nuisance of themselves. These are the ghosts that get into Maggie’s book. The poltergeists, the pet-scarers, the wailers, the literal-minded show-offs who dwell forever in the moment of death, the drowned melters, and then the really dangerous spirits who opt for undeath. By which I mean, yeah, they’re dead but screw this incorporeal nonsense. Whatever it takes to regain at least a semi-material semblance of life, they’re doing it.

We’re all well-acquainted with that “grosser” vampire which clings to earthly existence by stealing the blood of the living. Blood’s an obvious candidate for the essence of life. It’s easy to get at, especially if you have fangs. Sure, it’s a bit messy, but it has the advantage of regenerating itself if the vampire’s smart enough to let victims recover between tappings. A sustainable resource!

Which breath isn’t, according to Maggie’s book. It states that “each life has only a certain amount of breath within it.” That’s harder to parse than the idea that a body only has a certain number of pints of blood available at a given time. First you have to separate breath from air, which is external to the breather. Number of breaths taken per life, that could work. Or cubic centimeters of air allowed in and out of the lungs in a lifetime? Still, the breath-stealer’s said to take an “infinite amount of breath with each swallow.” Thinking logically, that means they would always kill with a single theft, right? Hyperkill!

The point probably is to stop thinking logically where breath-stealers are concerned. They’re ghosts. It’s a mystery, with mysterious laws. God, just relax and enjoy the story for its eerie beauty.

Okay, I will, and I have, very much. The demon lover who seduces only to destroy, that’s a great trope, and one at the center of both Agatha and Alex’s stories. Agatha’s take on it is more straightforward, Gothic-poetical, from the diction set a century or more in the past. Alex’s take is contemporary down to the easy of-the-moment dialogue. It’s also complicated by the emotional wreckage left behind by his wife’s death. Is Alex really in love with Agatha the spiky-punky barista, or is he in love with the idea of the tragic heroine who dies for love? And with the idea of dying for love, of giving in to the cosmic cycle of birth and death. Significant that the only comfort he finds after his wife’s death is the monk’s teaching that goddess Kali represents both womb and grave. Beginning and end.

Only now, in the middle of this particular cycle, Alex is suffering beyond endurance. Aesthetically sensitive, he shrinks from killing himself in the usual crass ways. But if he could go from ecstatic first kiss to tender floating death, a “fall into a black place like no other,” now that would be a consummation worth tossing Agatha into the drink for. So long as his gamble paid off and proved her a ghost, which it did.

Last thoughts about breath-stealers. I’m intrigued by the Chinese jiangshi, a kind of zombie-ghost that sucks the vital energy qi by way of its victim’s breath. This night-horror’s also called a hopper, because it’s too stiff to walk. Visualizing that, I’m both amused and the more terrified. As for cats. Folklore often accuses them of sucking the breath out of babies. All I know is my cat used to steal my breath by lying on my chest at night. He was meaner than Agatha, though, because when breakfast time came, he’d sink a claw or two into my nose.

Cats versus ghosts. Cats win, as usual.

Next week, a somewhat more lighthearted take on ghosts in E.F. Benson’s “How Fear Departed From the Long Gallery.” We may be retroactively doing a Halloween theme here.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.